by Alberto Freire | Jan 14, 2021 | COVID-19

Earlier pandemics had a huge effect on how cities were designed. The COVID-19 pandemic promises to do the same for offices.

As the pandemic surges on, businesses must reconsider their office building designs, looking for ways to improve traffic flow and upgrade their ventilation and airflow systems. Implementing necessary changes may be an issue for some businesses, but it’s a crucial task just the same. As Elvis Garcia, DrPH, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design says: “Let’s not fool ourselves. This is not the last virus we’ll face.” Watch the video to learn more about how COVID-19 may reshape office spaces.

Sam Omans, Architecture Industry Strategy Manager, Autodesk: Pandemics have had an enormous impact historically on architecture. If you’ve been to Manhattan, it’s got these straight gridiron streets. Those emerged during the 1800s as a response to health concerns associated with sewage, associated with light, associated with air. By building straight streets, you can build sewers right under the street. Earlier pandemics, flus, and contagions were understood to be associated with things like water and waste. So moving those out of the city and bringing light and air into the city became, from the 19th century forward, an enormous consideration in city planning.

Elvis Garcia, DrPH, Lecturer, Harvard Graduate School of Design: The office, by default, is not a safe environment. We are talking about an enclosed space with air circulation, with people inside, so we have to learn how to live with that because—let’s not fool ourselves—this is a virus, but it’s not the last virus we’ll face.

Lilli Smith, AIA, Senior Product Manager, Autodesk: There are certain points of interest in an office: coffee, bathrooms, exits, places where people’s paths lead. It’s important to analyze how those paths cross, where there could be congestion.

Pete Thompson, Senior Principal Engineer, Autodesk and Adjunct Lecturer, Lund University: What’s changed in the current pandemic conditions is that one-way flow is now really required in many aspects, just to try and keep people that radius of 6 feet, or 2 meters, or a meter further apart in all directions. So different aspects of technology can help in implementing those new routes and planning.

Garcia: One of the biggest challenges for people is organizing the traffic flow within the offices.

Smith: There’s a lot of thinking in offices around spacing for social distancing.

Thompson: When you’re planning office space, the default position of people is just to mark a grid on the floor and start from there. That doesn’t accommodate the fact that if you lay it out as 6 feet apart for each point, it doesn’t include the body size of people. And it also doesn’t allow people to walk in between each other, either.

For a regular doorway, you get about 130 people a minute through in “normal times.” For social distancing, that’ll drop to 25, 30 people a minute, but it’s a 75% drop in flow rates. And people need to be aware that when they’re planning on people going in or coming out of their building, it’s going to take a lot longer.

Garcia: Another important parameter is ventilation and airflow. It would be easier, yes, to just to open the windows and that’s it, because it will reduce the amount of viral load in the air. It’s not that straightforward. This has to come together with some more complex systems like air purification with specific filtering systems in place. It’s true that many offices don’t have the possibility to open windows. I think it’s an issue—it’s a problem for offices—the fact that they need to really upgrade their ventilation systems and their airflow systems.

Thompson: It’s a little easier than it would have been 15 years ago to plan for some of these requirements in 3D space for buildings. We’ve got digital tools available to us, so the designer can use things like Building Information Modeling packages like [Autodesk] Revit, where you can design the 3D space and lay out all those pathways.

Smith: Just as the pandemic was in full force, we released our generative-design tools. They allow you to encapsulate your design ideas and a system for how your design is going to work. So in the case of a restaurant, you’re looking at the spacing of the tables and making sure that it’s safe for restaurant patrons. But you’re also looking at the number of tables that you have, and is that going to be enough tables to make my restaurant still economically viable?

The consideration of spacing was always important, and that’s why it was part of our pre-pandemic plan for these tools. Being able to easily adjust that spacing is something that we can do. So it turned out to really be a good system that we could use for a purpose that we never envisioned.

Garcia: Technology can help us to adapt whenever new discoveries are made. And if we discover that this virus is spread in a different way, then we can adapt technology very easily to produce solutions that we can use. Otherwise, we will have to start from scratch. So I think technology can help a lot when trying to adapt very fast to new scenarios that come with new knowledge of the virus.

Omans: Throughout history, we’ve moved from closed offices to cubicles to totally open-plan offices, with as many people in them as possible. And what we’ve seen, if you look at the history, is that worker satisfaction has gone down actually. So this is an opportunity to bring worker satisfaction up and to reinvent the culture of the space.

Garcia: I believe this is a tipping point, and I believe that people are realizing that the way we inhabit spaces has a direct impact on health. It has to be far beyond a single virus. It’s more about how we live and how this technology can help us to understand the way we are building and how we can decrease the impact of the built environment on our health.

by Alberto Freire | Jun 10, 2020 | ARCHIBUS, COVID-19

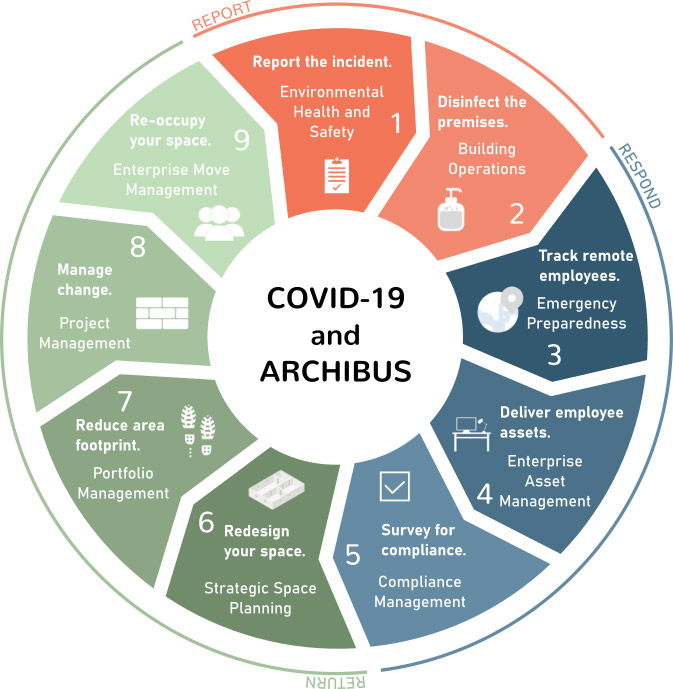

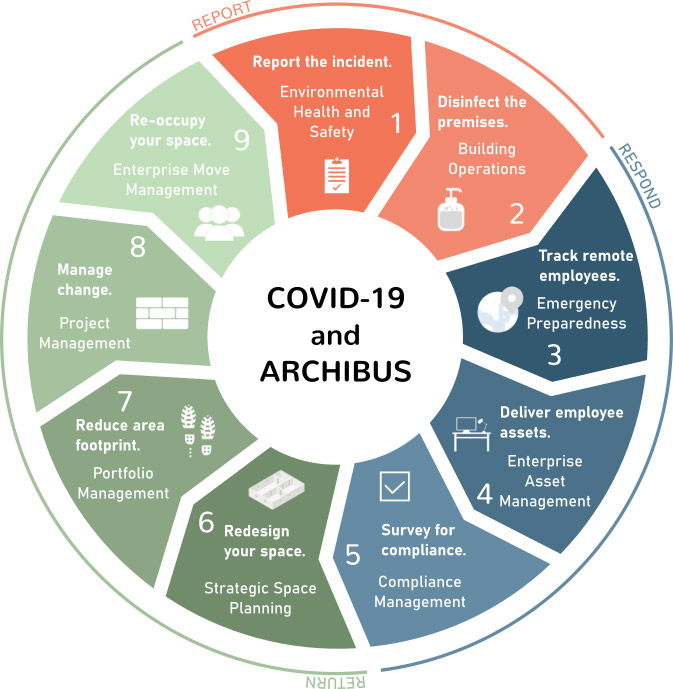

The nine stages of how to track coronavirus with Archibus. In this article:

Report

- Report the incident. (Environmental Health and Safety)

- Disinfect the premises. (Building Operations)

Respond

- Track remote employees. (Emergency Preparedness)

- Deliver employee assets. (Enterprise Asset Management)

- Survey for compliance. (Compliance Management)

Return

- Redesign your space. (Strategic Space Planning)

- Reduce your footprint. (Portfolio Management)

- Manage change. (Project Management)

- Re-occupy your space. (Enterprise Move Management)

Get to know the Workplace Maven Alliance. The Workplace Maven Alliance (WMA) is excited to be starting our new Knowledge Series, “COVID-19 in 1.9 Minutes”. Today’s article is an introduction to the series and will give the audience the following:

- A broad overview of the content that will be covered.

- How the WMA has broken up the coronavirus into three main stages and nine steps within that.

- A quick description of each stage, each step, it’s Archibus application, and why that application is beneficial to a company.

Our purpose in this series is to demonstrate how Archibus is the only IWMS that can comprehensively track every stage and step in the process of responding and recovering to a coronavirus incident in any organization. Because of its well-established customization capabilities, it can mold to any need an organization may have. This allows it to be the IWMS that can answer that can track any and all stages of a health and safety incident, no matter how an organization decides to split up the stages. We’ve decided to split up coronavirus reporting, responding, and returning stages into nine steps that we think every company will experience when preventing exposure to the virus. Every solution in the steps discussed can be accomplished with a standard, out-of-the-box, no-customization-required Archibus license.

Report.

The steps in this stage are the steps taken in the initial phase of being exposed to coronavirus, or taking preventive action to stop its spread.

1. Report the incident with Environmental Health and Safety.

Let’s say that someone in an organization starts showing symptoms of the coronavirus during the workday. What is the organization’s health and safety management plan? Is there one in place, or does one need to be created? How are all stakeholders in the incident going to be notified of the response protocol so every safety step is executed? Archibus Environmental Health and Safety allows incident management personnel to answer these questions, relay necessary safety information, and inform all stakeholders as quickly as possible upon reporting an incident. The application allows staff to create a report and fill in basic and granular information about the incident:

- where and when it took place

- any assets that were involved or affected

- the type of incident (in this case coronavirus)

- who was affected by the incident

- who responded to the incident

- what the response was

- medical information and tracking

- employee training for future incidents of this type

The strength of Archibus Environmental Health and Safety in this step is integration and connectivity; the software will pull in existing data—such as employee and location data, asset information, work order management, and more—to make the reporting process faster, easier, and more accessible to essential, key players. What’s more, this application is currently free. Visit the landing page for more details, and talk to your Archibus provider to learn how to implement.

2. Disinfect the premises with Building Operations.

Once you’ve reported an incident, immediate action needs to be taken to take care of any consequences from the incident—in the case of coronavirus, a thorough disinfection of any affected areas. Archibus Building Operations provides comprehensive capabilities for properly responding to incidents instantaneously. Using this application allows users to complete actions such as:

- Automatically generating a work request to clean the area.

- Sending a work request through the proper Service Level Agreement (SLA) to either speed up the completion process or guarantee that it gets the proper permissions.

- Responsive/mobile functionalities for instant update on work order status, records, schedules, and more.

- Creating location-based preventive maintenance schedules and procedures so that a location is cleaned and disinfected regularly, meeting any organizational or governmental requirements.

- Keeping a record of cleanings and maintenance procedures for inspections.

Leveraging the cause code within a work request allows users to quickly indicate whether a work request is related to a COVID incident without having to write a detailed description of such. We highly recommend this feature because it reports can be generated from this data, allowing an organization to understand how many incidents have occurred that are related to COVID-19. A feature that we have found sometimes gets underutilized is the reference documents. This can be used to provide a standardized process for carrying out work orders, such as disinfecting and cleaning, so quality is maintained, and health and safety can be certain.

Respond.

This stage involves the steps that allow an organization to take appropriate measures in keeping their employees safe and healthy.

3. Track remote employees with Emergency Preparedness.

Archibus Emergency Preparedness provides users with features to take appropriate preventive action, whether an incident has occurred recently or not. Pertaining to the COVID pandemic, some use cases we’ve found that are what Archibus excels at are:

- Tracking an employee’s previous location in the workplace and whether they are assigned to work from home.

- Using bulletins to notify when a building has returned to usability.

- Determining who has evacuated and who hasn’t, should an evacuation, whether gradual or immediate, be necessary.

4. Deliver employee assets with Enterprise Asset Management.

Archibus Asset Management tracks how many assets an organization has, in what condition they are, where they are located, who uses them, and much more. In the context of the coronavirus, this application can be a game-changer by:

- Ensuring that remote employees have a complete and ergonomic setup in their at-home offices.

- Whether your organization already has the equipment needed to supply at-home work spaces.

- Understanding space utilization for future reporting.

Space utilization can come into play here, as it is connected to the asset and employee that is being tracked.

5. Survey for compliance with Compliance Management.

The next application, Archibus Compliance Management complements Asset Management extremely well in the context of COVID-19. Compliance Management can help users determine and maintain employee health and safety while they are working from home. The application uses surveys to take the assumption out of determining whether remote employees have access to necessary equipment, such as:

- Software

- Hardware

- Ergonomic chairs, desks, stands, keyboards, mice, etc.

- Access to necessary servers, websites, and other remote locations.

Users can also send instructions to remote employees to ensure that they are taking care of themselves, such as:

- Taking proper breaks.

- Drinking enough water.

- What type of ergonomic equipment they should invest in and why.

- Virtual meeting tips, equipment, and software.

Surveys are extremely flexible. Users can customize all questions, response types, documents and instructions within a survey, as well as the geographic locations that will receive it or affiliation with a specific organization, should this be necessary. Senders can then view summary reports to understand how certain questions were answered, giving greater insight into an organization.

Return.

The following steps will aid an organization in executing their recovery plan so everyone can return to full productivity, whether that be through a restack of all facilities, a larger percentage of staff working from home, or a complete return to the original setup before COVID-19.

6. Redesign your space with Space Management and Strategic Space Planning.

Many corporate and institutional facilities professionals are wondering what buildings and offices will look like when the workplace reopens. Much discussion is revolving around how organizations can create workspaces that promote both productivity and employee safety. Archibus Space Management applications can be of help in every back-to-work strategy: analyzing, designing and optimizing existing workplaces to accommodate returning employees, and creating a sustainable workplace management plan. These applications provide users with space categorization, department allocation, and occupancy information, synchronized with AutoCAD floorplan drawings.

- Review and evaluate existing data and conditions

- Analyze space density and new capacity requirements

- Review occupancy requirements for Day-1 and beyond

- Optimize layout & design space complying with 6’ physical distancing

- Develop occupancy scenarios and schedule Moves (phases?)

Archibus Strategic Space Planning offers scenario planning which allows users to create floorplan schemas in AutoCAD without changing or editing the existing floorplate. Common changes that organizations make include modified furniture, tenant improvements, rearranged furniture and reassigning spaces between divisions and departments. Archibus Strategic Space Planning excels at:

- Identifying space requirements by number of people, area inventory and types of rooms

- Automatically running scenarios based on specific requirements, like the ones above, allowing organizations to maintain portfolio requirements for the next three-to-five years.

- Analyzing a portfolio and determining the types of space an organization owns, which are being completely used, and which have space to use. For example, let’s say an organization owns a space that is a warehouse for two months out of the year, but is left empty the other 10 months. Can an organization leverage that space, cut costs, and even save money?

In summary, the Archibus Space Management and Strategic Planning applications can play a critical role in this step by tracking space categories, allocation and occupancy, which are key factors when redesigning and restacking your space. This alone will encompass about 80% of the back to work requirements.

7. Reduce area footprint with Portfolio Management.

Real estate is usually the second biggest expense for an organization. How does an organization reduce its portfolio for cost savings while restacking floorplans to maintain social distancing? Archibus Portfolio Management gives an organization a detailed view into their real estate portfolio so strategic, cost-saving decisions can be made. Hand-in-hand with Strategic Space Planning, these two applications can help organizations determine exactly where they can save money by re-using or re-organizing space, leasing or subleasing space, buildings, and campuses, and much more. Some features that the application provides are:

- Global Portfolio dashboard, which will summarize portfolio and lease costs by geographic location, types of space (such as office, warehouse, manufacturing, etc.

- Cost Reporting, which will summarize and predict how much money an organization spends on real estate so they can forecast the next three to five years and achieve financial and space goals together.

- Create custom metrics within Archibus to build what-if scenarios.

- Use category and type to understand how you can reduce your area footprint, sublease, sell, reconfigure, or repurpose.

8. Manage change with Project Management.

Archibus Project Management allows organizations to organize and execute the space planning and portfolio projects discussed above: restacking and repurposing space, changing floorplates, and moving divisions, departments, and business units for cost effectiveness. Project Management allows users to:

- set up bid packages

- send bid packages to contractors

- track the bid

- select a bidder

- track project progress with Gantt charts

This application shares information with Archibus Capital Budgeting. All the information for the basic steps of a project—identifying a project, detailed analysis, building out tasks, milestones, determining a team, initial baseline costs, and design costs—can be linked back to the capital budget. The application will then help managers determine what tasks need to be addressed first, the budget for each task, and where any remaining budget can be allocated. Condition Assessment projects can also be bundled up in the same process above in Project Management, run through Capital Budgeting to define cost parameters, and then executed and finalized in Project Management. Archibus Environmental Sustainability Assessment and Archibus Clean Building also integrate well with this application to help organizations manage any COVID-19 related building projects by project priority and cost. AutoDesk has released many applications and plugins that complement this application well. Talk to your Archibus provider for more information about this.

9. Re-occupy your space with Enterprise Move Management.

Provides flexible solutions for returning to the workplace and maintaining social distancing; for example, instead of completely restacking a floorplate, an organization could decide to have every third desk enter the workplace on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, rotating employees on those days until the pandemic is resolved. Other phase approaches are possible and limitless. Many organizations have discussed the idea of only having 25% or 50% of their on-site workforce returning to the office space. Archibus Enterprise Move Management makes this phase approach effortless by:

- Creating flexibility by allowing the user to manage single and group moves

- Recording moves and changes through tickets

- Scheduling moves by generating work order tickets

- Coordinating all involved groups in the move process

- Mobile/responsive functionality for verifying staff’s assigned locations

Archibus Reservations can add functionality by allowing users to create windows linked to work orders between moves and room usage for routine disinfecting to take place. Archibus Hoteling will also let users stagger hotel space usage; for example some hotel spaces, spaced out for social distancing, could only be available during Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, while others could be available Tuesday and Thursday to allow a disinfection period. Returning to the Strategic Space Planning step we discussed above, the scenarios created in the Space Planning application can be migrated into a Move Management project. One click of a button will make this scenario into a move project, saving users time, money, and energy.